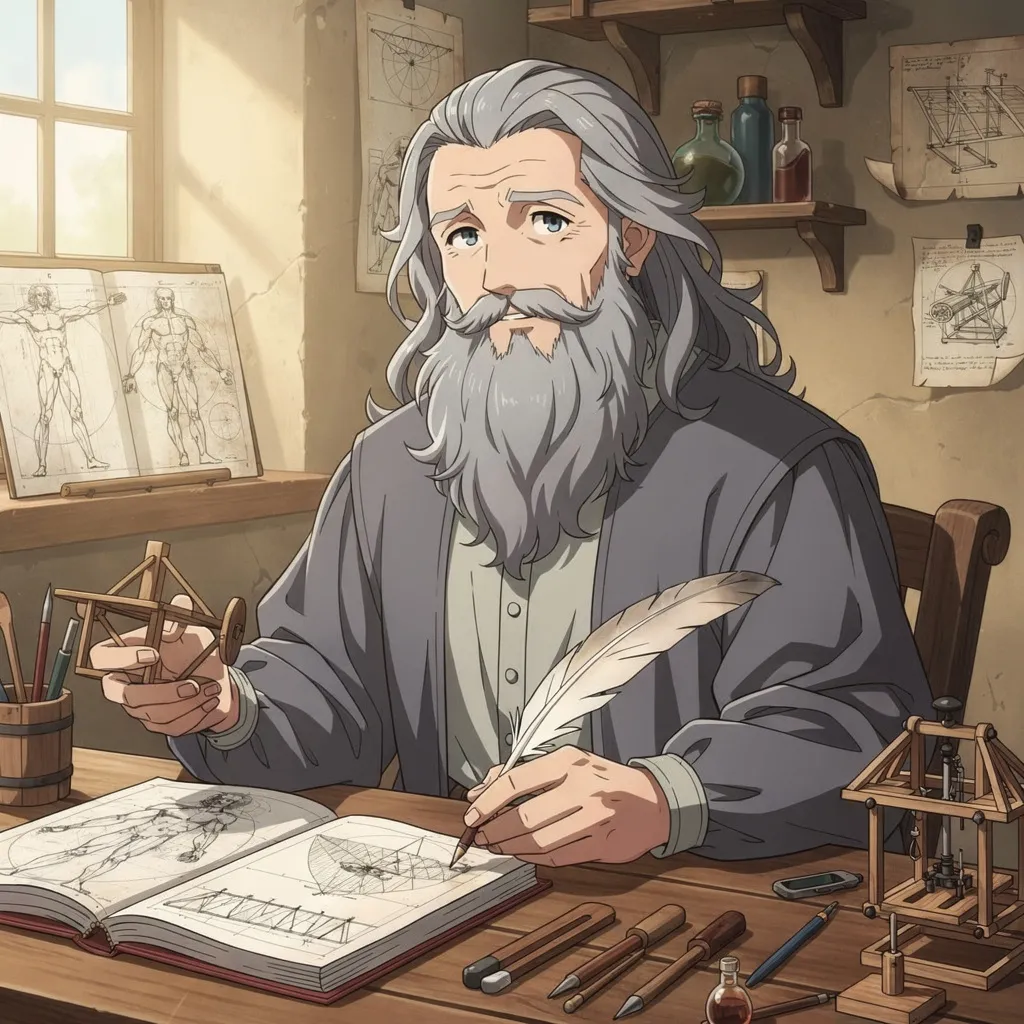

Leonardo da Vinci

1452-1519

He was a brilliant artist and inventor who loved learning about how the world works.

Early Life

Leonardo da Vinci was born in 1452 in a small town in Italy called Vinci. As a child, he was very curious and loved nature, drawing, and asking questions.

He did not go to a regular school for very long. Instead, he learned by watching the world around him and by practicing his skills every day.

Curiosity and Learning

Leonardo believed that learning never stops. He studied many subjects, including art, science, math, music, and the human body.

He carried notebooks everywhere and filled them with drawings and notes. He even wrote some of his notes backward, like a mirror, just for fun and challenge.

Art and Inventions

Leonardo is best known as a painter, but he was also an inventor and engineer. He drew ideas for flying machines, bridges, and tools long before they could be built.

Many of his inventions were never made during his lifetime. Still, his ideas helped future scientists and inventors think in new ways.

Famous Works

One of Leonardo’s most famous paintings is the *Mona Lisa*. People love her mysterious smile and the careful details in the painting.

Another important artwork is *The Last Supper*, which shows a famous moment from a story many people know. Leonardo used new painting methods to make his art look more real.

Legacy

Leonardo da Vinci is remembered as a "Renaissance Man," which means someone who is good at many things. He showed the world that art and science can work together.

Today, people still study his drawings and paintings in museums. His curiosity and love for learning continue to inspire kids and adults everywhere.

🎉 Fun Facts

Leonardo loved animals and was kind to them.

He wrote many notes backward so they could be read in a mirror.

He designed a flying machine inspired by birds.

The Mona Lisa is one of the most famous paintings in the world.

Leonardo was left-handed, which was unusual at the time.