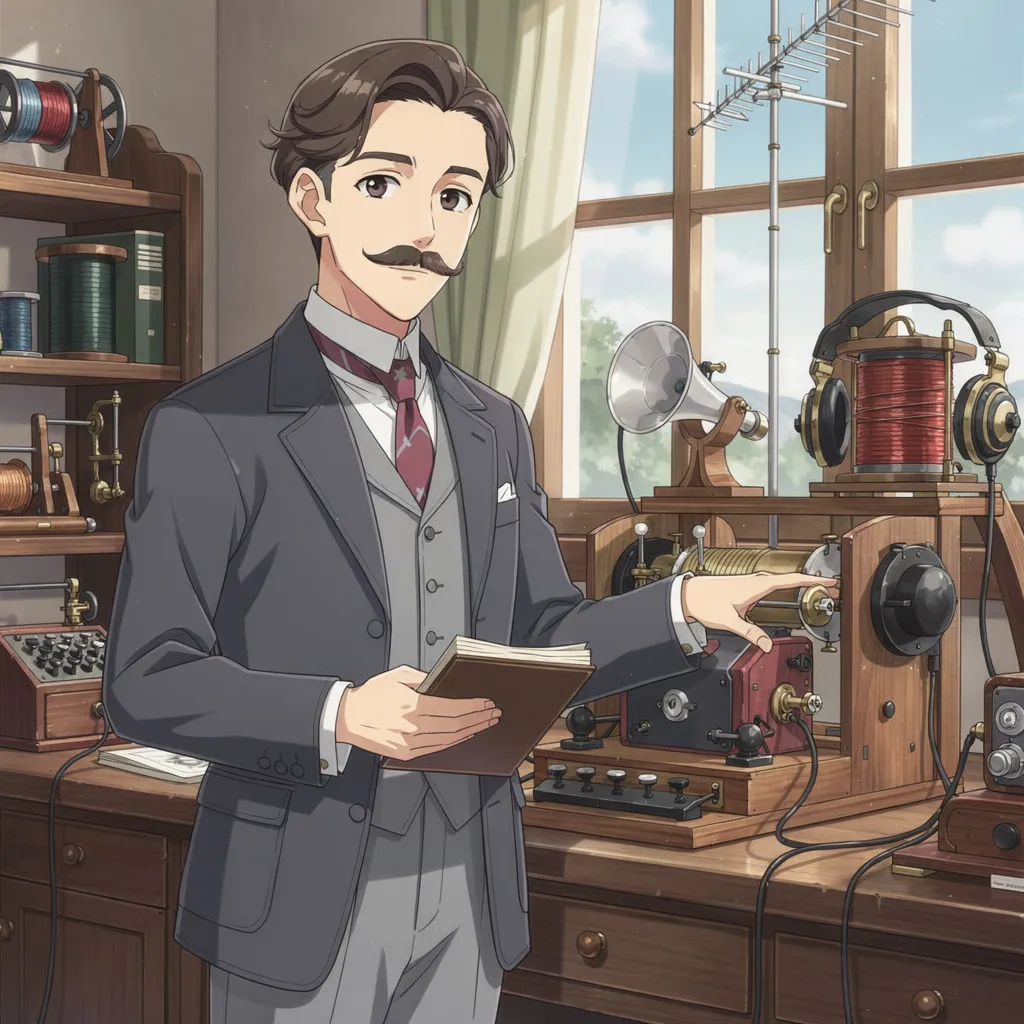

Guglielmo Marconi

1874-1937

Inventing early wireless radio technology that allowed messages to travel through the air.

Early Life

Guglielmo Marconi was born in 1874 in Bologna, Italy. As a child, he was very curious and loved learning how things worked. He enjoyed science experiments and spent a lot of time reading about electricity and signals.

Marconi did not always enjoy regular school lessons, but he loved learning at home. With the help of books and teachers, he learned about waves and electricity. These ideas would later help him change the way people communicate.

A Big Idea

In the late 1800s, sending messages over long distances was slow and difficult. Marconi wondered if messages could travel through the air without wires. This was a bold idea at the time!

He began experimenting in his family’s backyard. Using simple tools, wires, and antennas, he sent signals farther and farther. Soon, his wireless messages traveled miles instead of just a few feet.

Amazing Achievements

Marconi’s biggest achievement was developing wireless telegraphy, which later became radio. In 1901, he sent the first wireless message across the Atlantic Ocean. This proved that signals could travel very long distances.

His invention helped ships communicate at sea. This made travel safer because ships could call for help in emergencies. People all over the world began using wireless communication.

In 1909, Marconi won the Nobel Prize in Physics for his work. This was a huge honor and showed how important his invention was.

Later Life

Marconi continued improving radio technology throughout his life. He worked with scientists and engineers in many countries. His inventions helped connect the world in new ways.

He passed away in 1937, but his ideas lived on. Radios, televisions, and even modern wireless devices are connected to his early work.

Legacy

Guglielmo Marconi is remembered as one of the fathers of radio. His curiosity and hard work changed how people share information.

Today, when we use radios, phones, or Wi-Fi, we are using ideas that began with Marconi’s experiments. His story shows that big ideas can start in small places.

🎉 Fun Facts

Marconi did many of his first experiments in his backyard.

He won the Nobel Prize when he was only 35 years old.

Marconi’s radio technology helped save lives at sea.

He loved experimenting more than sitting in a classroom.

Many people call him the "father of radio."